The Body’s Non-specific Response to Stress

Sometimes discovery is serendipitous. Today I was searching for new articles on a phenomenon called “sickness behavior” and chanced on an article entitled “Between being healthy and becoming comatose: the neuropsychiatric landscape of critical illness with a focus on delirium, DSM-5 and ICD-11.” Not beach reading, but what I found there blew my mind. Here’s why:

Nearly a century ago, Hans Selye, the father of modern stress theory, defined stress as “the body’s non-specific response to any demand made on it.” As is often the case, Selye’s definition raises its own questions. What is a non-specific response? Is it one thing, or lots of things? If it’s predictable and generic, how did we end up with 50,000+ diseases and syndromes?

Selye’s original forumulation of stress theory, called General Adaptation Syndrome, had a three-stage generic response:

- Alarm

- Resistance

- Fatigue

If the stressor didn’t resolve or lessen, the fatigue stage descended into critical illness and death. That’s a useful if broad outline, but Selye spent his career documenting in detail how the body’s hormonal systems responded to stressors. Much of what we know about the body’s central stress response—the activation of the HPA Axis, the release of cortisol and adrenaline, the activation of the sympathetic nervous system and the immune system—stem from Selye’s foundational work. His General Adaptation Syndrome sparked a vigorous debate in the halls of medicine, but by the early 1950s his work was largely marginalized in clinical medicine (hence the 50,000+ diseases and syndromes), despite becoming mainstream in psychology and sociology. Stress, for doctors, became “just stress.”

Enter Sickness Behavior

Despite the cold shoulder from clinical medicine, stress research continued, buttressed by rapidly expanding understanding of bodily systems and how they work and break down in disease. In the early 90s, researchers began studying a phenomenon called “sickness behavior,” a collection of behaviors designed to ensure you don’t conduct business-as-usual when you are sick. They included heightened sensitivity to pain, fever, fatigue, anxiety, depression, social isolation, loss of appetite, loss of interest in daily activities and grooming.

While the initial research focused on infections, the researchers discovered something striking. The same sickness behaviors associated with infections were also induced by injury, surgical recovery, chemotherapy, and psychological stress. Furthermore, they found the underlying mechanism that caused them—neuroinflammation caused by rising IL-1B and IL-6 levels. Think about it. A huge swath of the symptoms we associate with disease and large chunk of what we think of as mental illness is a generic response to stress (any demand on the body) and sufficient downstream immune system activation and inflammation to activate the behaviors. Selye scores again!

On to the Article

I’ve been so taken with sickness behavior and its ramifications for how we understand stress and disease that I took my eye off the ball regarding other generic manifestations of the stress response. Then I read the article. The authors are psychiatrists and their article critiques the two major disease classification systems, ICD-11 (the WHO International Catalog of Diseases) and DSM5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, v5). Nothing exciting yet. Their beef is that neither classification system has acknowledged the concept of critical illness, let alone it’s importance in common neuropsychiatric symptoms. They’ve got my attention. They go on to discuss the 10 most common neuropsychiatric symptoms in critical illness:

- Fever

- Sickness behavior

- Executive function problems

- Epilepsy

- Hyperactive delirium

- Acute apathy syndrome (a more appropriate name than hypoactive delirium)

- Catatonic agitation or inhibition

- Refractory agitation or inhibition

- Coma

- Death

Now I’m excited. Rather than go into the details of what each of those symptoms entail, I’ll simply note that the authors are pointing to generic symptoms in critical illness coming at Stage 3: Fatigue of Selye’s General Adaptation Syndome. I’m excited because I’ve generally thought of sickness behavior appearing at the earlier Alarm and Resistance stages. The authors, perhaps intuitively, are pointing to the importance of understanding the body’s generic behaviors and pathologies at every stage of the the stress response. They’re also modeling that it’s possible to identify those behaviors and prepare for them, whether you’re a team of critical care specialists, or just a health consumer trying to prevent the stress cycle from advancing to more severe stages.

While a serious treatment of all the behaviors would make a good, long book, there is some low-hanging fruit worth mentioning, precisely because it’s not getting the clinical attention it deserves. Let’s look at them by stage:

Stage 1: Alarm (Perceived or actual threat, stressor)

- Central Stress Response/HPA Axis activation

- Cortisol released

- Catecholamines released (e.g. adrenaline)

- Sympathetic Nervous System activated (Fight or Flight response)

- Resource directed away from reproduction and digestion to muscles energy production and hypervigiliance

- Neuroimmune system activated (e.g. Microglia)

- Neuroinflammation, redox stress

- Immune system activated

- Inflammation, redox stress

- Magnesium expelled from your cells to your serum

- Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone system activated

- Aldosterone levels rise

- Endocannabinoid system activated with bidirectional effects on the HPA axis

- Cellular Stress Response activated

- Heat shock/cold shock proteins activated

- Unfolded Protein Response activated

- NRF2 upregulated to enhance cellular redox state

- AMPK upregulated to maintain energy balance

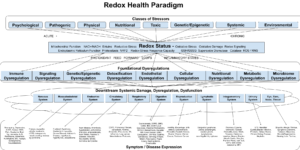

Stage 2: Resistance (The stress response over time is effective or ineffective, adaptive or maladaptive)

- Nutritional Stress. Raw materials are consumed or lost in the stress response and either replaced through diet/supplementation (adaptive) or diminished (maladaptive) with loss of function in multiple systems.

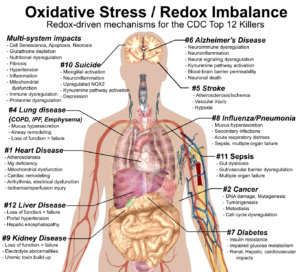

- Redox Stress. Redox pools are either enhanced and maintained by NRF2/AMPK activation (adaptive) or diminished and dysregulated (maladaptive) by elevated or chronic stress leading to pathological signaling, symptoms and disease

- Autonomic Nervous System stress. Sympathetic/Parasympathetic systems are sufficiently balanced to repair stress-related damage (adaptation) or Sympathetic/Parasympathetic systems are dyregulated leading to chronic sympathetic hyperactivation, hypertension, autonomic dysfunction, digestive disorders, cardiometabolic issues, etc.

- Endocannabinoid Stress (ECS). The ECS participates in healthy regulation of the stress response (adaptive) or Endocannabinoid tone is diminished leading to intestinal permeability, mental health issues, pain, etc.

- Metabolic Stress. AMPK activation maintains healthy energy production and resilience against stressors (adaptive), or redox stress damages mitochondrial number/health, impedes energy production, insulin sensitivity, glucose tolerance, energy balance.

- Immune Stress. The immune system mounts an effective response to destroy pathogens and damaged cells, heal damage and returns to a quiescent state (adaptive), or the immune system mounts an ineffective response, remains active and promotes systemic inflammation and redox stress (maladaptive), leading to accelerated aging, symptoms, and disease

- Neuroendocrine Stress. Metabolic status, redox status, neuroendocrine status are maintained at a level that supports healthy brain function (adaptive), or dimished metabolic status, redox status, immune status, nutritional status, encannabinoid tone, causes diminished memory, cognitive, mood status, neurodegeneration and neuropsychiatric issues.

- Microbiome Stress. A healthy microbiome positive regulates all other organ systems (adaptive), dysbiosis leads to inflammation, intestinal permeability and pathological signaling with other organ systems (maladaptive)

Stage 3: Fatigue (The capacity to mount a useful, effective adaptive response is diminished. Stage 3 is an accelerated aging state.)

- Organ systems are characterized by damage, dysregulation and loss of function, leading to systemic stress and ultimately multiple organ failure and death

- Stress responses are increasingly maladaptive, including

- Tissue fibrosis

- Bone loss

- Muscle loss

- Mitochondria loss / damage

- Loss of gut and vascular barrier function, blood-brain barrier permeability

- Self-sustaining or self-amplifying pro-oxidant, pro-inflammatory states

- Immunoincompetence or hyper-reactivity

- Central stress response no longer shuts down

- Shortened or low quality sleep

- Ineffective detoxification/loss of function in liver and kidneys

- Cells are increasingly exhibiting the hallmarks of cellular aging, all of which are redox stress-driven

- Genomic instability

- Telomere attrition

- Epigenetic alterations

- Loss of proteostasis

- Deregulated nutrient-sensing

- Mitochondrial dysfunction

- Cellular senescence

- Stem cell exhaustion

- Altered intercellular communication

- The descent into critical illness increases risk for health crises, chronic disease, cancer, falls, loss of function, and frailty

- Critical illness involves manutrtion, redox stress, inflammation, immunosenescence, immunoincompetence and hyper-responsiveness (e.g. the cytokine storm), loss of barrier function and neuropsychiatric involvement as discussed in the article.

Looking at that (admittedly partial) list, it can seem rather dark. But the promise of all the progress we’re making in understanding the body is earlier intervention to bolster stress resilience, minimize or mitigate stressors, and thus preventing or delaying disease. And that’s worth getting excited about!